Dear friends,

Today, March 11, we commemorate the 7th anniversary of the Fukushima nuclear accident.

The government of Japan has admitted that the process of removing the irradiated cores from the three crippled reactors will take at least forty years. We are concerned that the Fukushima nuclear crisis will affect human and environmental safety for many years afterward. Experts worry that the forty-year flow of the radioactive wind and contaminated water are reaching North America.

The Middle East and China are beginning to get more nuclear power plants, which many believe will be a major help for climate change. But what risks are we creating through nuclear development?

Nuclear disasters need not have natural origins Before long, we may see terrorist or cyber attacks on nuclear power reactors, whether in Europe, the Middle East, or elsewhere. If this occurs at one of France’s 18 nuclear power stations, for example, huge areas of Western Europe – cities and farms alike — will become uninhabitable for many years.

Political leaders, business leaders, religious leaders, scientists, universities, and environmental organizations such as the Sierra Club should bring their global perspectives to the immediate, specific problem of Fukushima.

In this regard, I am pleased to introduce two articles that cover the essence of the nature of the nuclear accident.

Akio Matsumura

——-

Fukushima Has Now Contaminated Over 1/3 Of the World Oceans ( And Its Getting Worse ) in Awareness Act

Most people do not realize the repercussions that disasters like the Fukushima nuclear meltdown have on the world. When it happens the media is all over it, and then soon they trickle off and nobody ever thinks about it again.

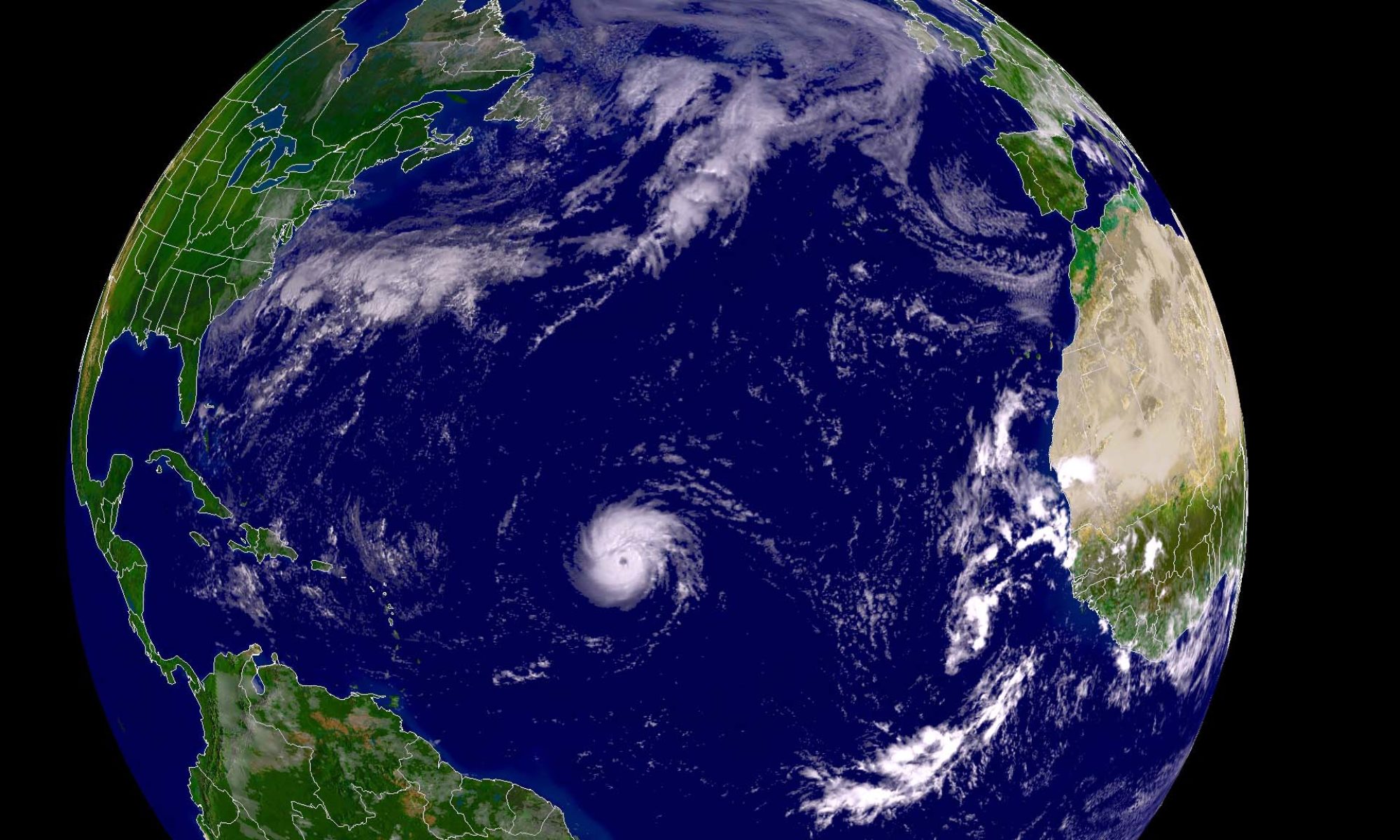

But the fact is, even though nobody is talking about it, it does not mean that the trouble is gone. Quite the contrary actually, the Fukushima disaster is still affecting the world today. Almost one-third of the globe is thought to have been contaminated from the leak out from the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster.

More than 80% of the radioactivity from the damaged reactors ended up in the Pacific Ocean, far more than reached the ocean from Chernobyl or Three Mile Island. Of this, a small fraction is currently on the seafloor, the rest was swept up by the Kuroshio Current, a Western Pacific version of the Gulf Stream, and carried out to sea where it mixed with the vast volume of the North Pacific.

These materials, primarily two isotopes of cesium, only recently began to appear in the Eastern Pacific. For example, in 2015 we detected signs of radioactive contamination from Fukushima along the coast near British Columbia and California. While these amounts are trace, the danger of radioactive material in any amount cannot be underestimated. Every possible exposure, in any small amount, adds up.

So what should we take from this? That it is incorrect to say that Fukushima is under control when levels of radioactivity in the ocean indicate that the leaks are ongoing. More than 1,000 tanks brimming with irradiated water stand inland from the Fukushima nuclear plant. Each day 300 tonnes of water are pumped through Fukushima’s ruined reactors to keep them cool.

The company that owns the plant, TEPCO, has deployed a filtration device that has stripped very dangerous isotopes of strontium and cesium from the flow. The water in the tanks still contains tritium and isotope of hydrogen with two neutrons. Tritium is a major by-product of nuclear reactions and is difficult and expensive to remove from the water.

Now, Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority has launched a campaign to convince a skeptical world that dumping up to 800,000 tonnes of contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean and is a safe and responsible thing to do.

I say, that any further dumping is done, the IAEA and Tokyo Electric Power Co., need to consider the impact that it is having on the environment. Entire livelihoods could be affected as well as the long-tern health of the region and eventually the global community.

7 Years on, Sailors Exposed to Fukushima Radiation Seek Their Day in Court

by Gregg Levine in The Nation

At over 1,000 feet in length and weighing roughly 100,000 tons, the USS Ronald Reagan, a supercarrier in the United States Navy’s Seventh Fleet, is not typically thought of as a speedboat. But on a March day in 2011, the Nimitz-class ship was “hauling ass,” according to Petty Officer Third Class Lindsay Cooper.

Yet, when the Reagan got closer to its destination, just off the Sendai coast in northeastern Japan, it slowed considerably.

“You could hardly see the water,” Cooper told me. “All you saw was wood, trees, and boats. The ship stopped moving because there was so much debris.”

Even after more then 20 years in the service, Senior Chief Petty Officer Angel Torres said he had “never seen anything like it.” Torres, then 41, was conning, or navigating, the Reagan, and he describes the houses, trucks, and other flotsam around the carrier then as “an obstacle course.” One wrong turn, he worried, “could damage the ship and rip it open.”

The Reagan—along with two dozen other US Navy vessels—was part of Operation Tomodachi (Japanese for “friends”), the $90 million rescue, disaster-relief, and humanitarian mobilization to aid Japan in the immediate aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. For the sailors, the destruction was horrific—they told me of plucking bodies out of the water, of barely clothed survivors sleeping outside in sub-freezing weather, and of the seemingly endless wreckage—but the response was, at first, something they’d rehearsed.

“We treated it like a normal alert,” Cooper said. “We do drills for [these] scenarios. We went into that mode.” She and her approximately 3,200 shipmates moved food, water, and clothing from below to the flight deck where it could be put on helicopters and flown to the stricken residents.

But that sense of routine soon changed.

“All of the sudden, this big cloud engulfs us,” Torres said. “It wasn’t white smoke, like you would see from a steam leak,” he explained, but it also wasn’t like the black smoke he saw from the burning oil fields during his deployment in Kuwait in 1991. “It was like something I’d never seen before.”

Cooper was outside with her team, on the flight deck, prepping before the start of reconnaissance flights. She remembers it was cold and snowing when she felt, out of nowhere, a dense gust of warm air. “Almost immediately,” she said, “I felt like my nose was bleeding.”

But her nose wasn’t bleeding. Nor was there blood in her mouth, though Cooper was sure she tasted it. It felt, she said, “like I was licking aluminum foil.”

On March 11, 2011, at 2:46 pm local time, a 9.1 magnitude earthquake struck about 40 miles east of Japan’s Oshika Peninsula. The quake, the world’s fourth largest since 1900, devastated northern Honshu, Japan’s main island. At the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, located near the epicenter on the Pacific coast, the temblor damaged cooling systems and cut all electrical power to the station—power that is needed to keep water circulating around the active reactor cores and through pools holding decades of used but still highly radioactive nuclear fuel.

Several of the diesel-powered emergency generators at Daiichi kicked in to restart some of the safety systems, but less than an hour after the earthquake a 43-foot-high wave triggered by the quake swept over the sea wall, flooding the facility, including most of the generators, some of which had been positioned in the basement by the plant’s designer, General Electric.

Without any active cooling system, the heat in the reactor cores began to rise, boiling off the now-stagnant water and exposing the zirconium-clad uranium fuel rods to the air, which set off a series of superheated chemical reactions that split water into its elemental components. Hundreds of workers from Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the station’s owner, struggled valiantly to find a way to circulate water, or at least relieve the pressure now building in the containment vessels of multiple reactors.

But the die was cast by the half-century-old design, with results repeatedly predicted for decades. The pressure continued to build, and over the course of the next two days, despite attempts to vent the containment structures, hydrogen explosions in three reactor buildings shot columns of highly radioactive gas and debris high into the air, spreading contamination that Japan still strains to clean up today.

And yet, despite this destruction and mayhem, proponents of nuclear power can be heard calling Fukushima a qualified success story. After all, despite a pair of massive natural disasters, acolytes say, no one died.

But many of the men and women of the Seventh Fleet would disagree. Now seven years removed from their relief mission, they’d tell you nine people have died as a result of the disaster at Fukushima Daiichi—and all of them are Americans.

Read the rest of the story, published March 8, 2018.

Thank you so much for all this invaluable information. I have posted an extract on my website today where there is also long article on the danger of nuclear reactors and also a book review of a book called Nuclear Weapons: an Absolute Evil which includes a section on the danger of nuclear reactors from terrorist attack.